IB Biology HL Study Guide: An Overview

IB Biology HL is a rigorous course demanding a deep understanding of biological principles, spanning from cellular processes to ecological systems․

This guide offers definitions, explanations, and example questions covering core topics like cells, DNA, genetics, and the IA components․

Success requires diligent study, practical skills, and a grasp of experimental design, data analysis, and effective scientific communication․

What is IB Biology HL?

IB Biology HL (Higher Level) is a challenging two-year course designed for students with a strong aptitude and genuine interest in the biological sciences․ It delves significantly deeper into complex concepts than the Standard Level (SL) course, demanding a more analytical and comprehensive approach to learning․

This course isn’t merely about memorizing facts; it emphasizes understanding the underlying principles governing life, from the molecular level to entire ecosystems․ Students will explore core themes like cell biology, molecular biology, genetics, ecology, evolution, and human physiology, building a robust foundation for further study in related fields․

The HL curriculum necessitates a substantial commitment to independent learning, practical work, and critical thinking․ Expect extensive laboratory investigations, detailed report writing, and a significant internal assessment (IA) component․ The IA allows students to design and conduct their own biological investigations, fostering scientific inquiry and problem-solving skills․ Successful completion prepares students for university-level biology programs and related scientific disciplines, equipping them with the skills and knowledge necessary for advanced study and research․

Scope and Demand of the Course

IB Biology HL possesses a broad scope, encompassing a vast array of biological disciplines․ The curriculum extends beyond foundational concepts, requiring students to explore intricate details within each core topic – cell biology, molecular biology, genetics, and ecology – alongside evolution and human physiology․ Expect detailed study of processes like DNA replication, membrane transport, and inheritance patterns․

The demand is substantial, requiring approximately 150 hours of instruction over two years․ This includes significant time dedicated to practical investigations, data analysis, and scientific report writing․ Students must demonstrate proficiency in designing experiments, collecting and processing data, drawing valid conclusions, and critically evaluating methodologies․

Furthermore, the course emphasizes the interconnectedness of biological systems․ Understanding how different concepts relate to one another is crucial․ The IA component adds to the workload, demanding independent research and a thorough understanding of scientific principles․ Success requires consistent effort, strong analytical skills, and a proactive approach to learning, preparing students for the rigors of university-level science programs․

Core Topics: Detailed Breakdown

IB Biology HL core topics include cell biology, molecular biology, genetics, and ecology․ Each area demands in-depth knowledge and practical application of key biological concepts․

Cell Biology

, examining the historical development of cell theory and the diverse range of cell types, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic․

Further exploration covers Cell Structure (1․2), requiring detailed understanding of organelle functions and their relationships within the cell․ Students will learn to draw and label cell diagrams accurately, demonstrating comprehension of structural components․

Membrane Transport (1․3) investigates how substances move across cell membranes, focusing on processes like diffusion, osmosis, and active transport․ Understanding membrane structure and its role in regulating transport is crucial․

Finally, Cell Respiration (1․4) unravels the metabolic pathways cells utilize to generate energy, including glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation․ This topic emphasizes the importance of ATP as the cellular energy currency and the role of enzymes in these processes․

establishes the fundamental principles underpinning all biological study․ This section traces the historical development of cell theory – the cornerstone of modern biology – highlighting contributions from scientists like Robert Hooke, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, and Rudolf Virchow․

A key focus is differentiating between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, understanding their structural distinctions, and recognizing examples of each․ Prokaryotes, lacking a nucleus, are contrasted with the complex, compartmentalized organization of eukaryotes․

Students must grasp the concept of surface area to volume ratio and its implications for cell size and efficiency․ This ratio dictates nutrient uptake and waste removal capabilities, influencing cell function․

Furthermore, the section explores the diverse range of cell types, including specialized cells within multicellular organisms, and their adaptations for specific roles․ Understanding these variations is crucial for comprehending tissue and organ function․

1․2 Cell Structure

Cell Structure delves into the intricate components that constitute both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells․ Students will meticulously examine the functions of organelles – specialized subunits within eukaryotic cells – such as the nucleus, mitochondria, ribosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and chloroplasts (in plant cells)․

A significant emphasis is placed on the plasma membrane, its phospholipid bilayer structure, and the roles of embedded proteins in regulating transport․ Understanding membrane composition is vital for comprehending cellular communication and material exchange․

The section requires detailed knowledge of cytoskeletal elements – microtubules, intermediate filaments, and actin filaments – and their contributions to cell shape, movement, and intracellular transport․

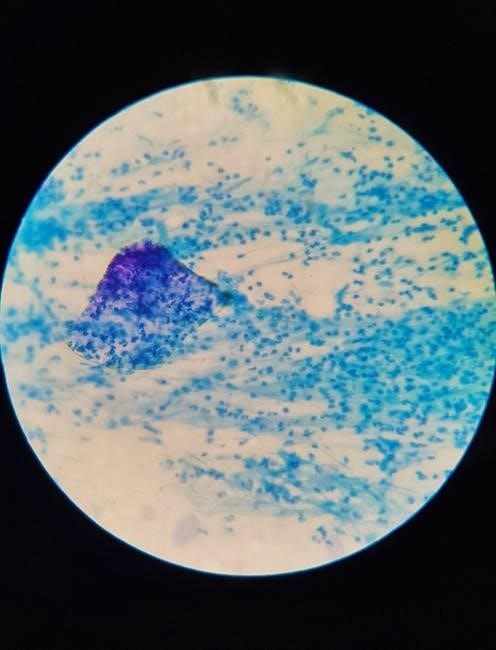

Furthermore, students must be proficient in drawing and labeling cell structures from both microscopic observations and diagrams, demonstrating a clear understanding of their spatial organization and interrelationships․ This skill is frequently assessed․

1․3 Membrane Transport

Membrane Transport explores how substances move across cell membranes, a crucial process for maintaining cellular homeostasis․ This section differentiates between passive transport mechanisms – diffusion, osmosis, and facilitated diffusion – which require no energy expenditure, and active transport, demanding ATP to move substances against their concentration gradients․

Students must grasp the principles governing osmosis and its impact on cells in hypotonic, hypertonic, and isotonic solutions․ Understanding water potential and its calculation is essential․

Detailed knowledge of transport proteins – channel proteins and carrier proteins – and their specific roles in facilitated diffusion and active transport is required․ The sodium-potassium pump serves as a key example of primary active transport․

Furthermore, the section covers vesicular transport – endocytosis (phagocytosis and pinocytosis) and exocytosis – enabling the bulk transport of materials into and out of cells․ Comprehending these mechanisms is vital for understanding cellular processes like nutrient uptake and waste removal․

1․4 Cell Respiration

Cell Respiration delves into the metabolic pathways cells utilize to convert biochemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s primary energy currency․ This section necessitates a thorough understanding of both aerobic and anaerobic respiration, highlighting their differences in oxygen requirement and ATP yield․

Students must detail the four key stages of aerobic respiration: glycolysis, the link reaction, the Krebs cycle (citric acid cycle), and the electron transport chain (ETC) coupled with oxidative phosphorylation․ Knowing the location of each stage within the cell is crucial․

Understanding the role of electron carriers like NADH and FADH2 in the ETC, and how proton gradients drive ATP synthase, is paramount․ The process of chemiosmosis must be clearly understood․

Furthermore, the section explores anaerobic respiration – fermentation – including lactic acid fermentation and alcoholic fermentation, and their respective ATP production․ Comparing the efficiency of aerobic versus anaerobic respiration is essential for a complete grasp of energy production․

Molecular Biology

Molecular Biology forms a cornerstone of IB Biology HL, focusing on the intricate molecular processes underpinning life․ This section demands a detailed exploration of the molecules essential for life and their interactions, bridging the gap between structure and function․

Key areas include the study of water’s unique properties and its role in biological systems, alongside the structures and functions of carbohydrates (sugars, starches) and lipids (fats, oils)․ Understanding their roles in energy storage and structural components is vital․

A significant portion is dedicated to proteins – their amino acid building blocks, diverse structures (primary, secondary, tertiary, quaternary), and crucial roles as enzymes․ Enzyme kinetics, including factors affecting enzyme activity, are essential․

Finally, the section culminates in a deep dive into nucleic acids – DNA and RNA – their structures, and the process of DNA replication․ Understanding Chargaff’s rule and the semi-conservative nature of replication are fundamental concepts․

2․1 Molecules to Metabolism

Molecules to Metabolism initiates the Molecular Biology unit by establishing the fundamental link between molecular structures and life’s processes․ It explores how the properties of biological molecules directly influence metabolic pathways․

This topic begins with an examination of the emergent properties arising from the unique chemical characteristics of water, crucial for its role as a solvent and temperature regulator․ It then delves into the four classes of organic macromolecules: carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids․

Students will analyze how these molecules are assembled from monomers and polymers, focusing on the dehydration and hydrolysis reactions involved․ Understanding the structural diversity within each class, and how structure dictates function, is paramount․

The section culminates in exploring how these molecules participate in metabolic reactions, including energy transformations and the building/breaking down of complex structures․ This lays the groundwork for understanding enzyme function and cellular respiration․

2․2 Water, Carbohydrates and Lipids

Water’s exceptional properties – cohesion, adhesion, high specific heat capacity, and versatility as a solvent – are central to life․ Its polarity enables hydrogen bonding, driving these characteristics and supporting biological processes․

Carbohydrates, encompassing monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides, serve as primary energy sources and structural components․ Students will examine glucose, fructose, sucrose, starch, and cellulose, noting their differing roles based on their molecular structures․

Lipids, including triglycerides, phospholipids, and steroids, exhibit diverse functions․ Triglycerides provide long-term energy storage, phospholipids form cell membranes, and steroids act as hormones and signaling molecules․

Understanding the saturated and unsaturated nature of fatty acids, and their impact on membrane fluidity, is crucial․ The hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties of lipids are also key to their biological roles․ Analyzing the structures and functions of these molecules provides a foundation for understanding metabolism․

2․3 Proteins and Enzymes

Proteins are complex macromolecules constructed from amino acid monomers, linked by peptide bonds․ Their diverse structures – primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary – dictate their specific functions, ranging from structural support to enzymatic catalysis․

Enzymes, biological catalysts, accelerate biochemical reactions by lowering activation energy․ Understanding enzyme structure, including the active site, is vital․ Factors influencing enzyme activity – temperature, pH, and substrate concentration – must be analyzed․

The ‘lock and key’ and ‘induced fit’ models explain enzyme-substrate interactions․ Enzyme inhibition, both competitive and non-competitive, regulates metabolic pathways․ Students will explore how these mechanisms control biological processes․

Denaturation, the loss of protein structure due to environmental changes, impacts enzyme function․ Investigating protein folding and the role of chaperones provides a deeper understanding of protein biology․ Comprehending these concepts is fundamental to understanding metabolism and cellular regulation․

2․4 Nucleic Acids and DNA Replication

Nucleic acids, DNA and RNA, are crucial for genetic information storage and transfer․ DNA’s double helix structure, composed of nucleotide monomers (sugar, phosphate, and nitrogenous base), is fundamental․ Chargaff’s rule – adenine pairs with thymine, and guanine with cytosine – governs base pairing․

DNA replication is a semi-conservative process ensuring genetic continuity․ It involves enzymes like DNA polymerase, helicase, and ligase, working in a coordinated manner․ Understanding the steps – initiation, elongation, and termination – is essential․

The replication fork, leading and lagging strands, and Okazaki fragments are key components․ Students must analyze the differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA replication․ Errors during replication lead to mutations, impacting genetic variation․

Exploring the role of DNA in heredity and the implications of mutations is vital․ Comprehending these processes provides a foundation for understanding genetics, evolution, and molecular biology․ The accurate replication of DNA is paramount for life․

Genetics

Genetics, the study of heredity, is a cornerstone of IB Biology HL․ This section delves into the mechanisms of gene inheritance, chromosomal behavior, and the causes of genetic variation․ Understanding genes, their structure, and function is paramount, alongside the organization of genetic material into chromosomes․

Meiosis, the process of cell division producing gametes, is crucial for sexual reproduction and genetic diversity․ Students must grasp the stages of meiosis and how they differ from mitosis․ Mutations, alterations in the DNA sequence, are also explored, examining their types and potential consequences․

Inheritance patterns, including Mendelian genetics (dominant/recessive alleles, monohybrid and dihybrid crosses), are essential․ Beyond simple Mendelian inheritance, students will investigate sex-linked traits, codominance, and incomplete dominance․ Analyzing pedigree charts is a key skill․

This topic connects directly to molecular biology and evolution, providing a framework for understanding how traits are passed down and how populations change over time․ A strong grasp of genetics is vital for success in this course․

3․1 Genes, Chromosomes and Mutations

This section focuses on the fundamental units of heredity: genes and chromosomes․ Genes, segments of DNA, code for specific traits, while chromosomes are structures containing tightly wound DNA․ Understanding their organization within the genome is crucial․

Chromosomal structure, including homologous pairs and sex chromosomes, will be examined․ Students will learn about karyotypes and how to identify chromosomal abnormalities․ The relationship between genes and alleles, different versions of a gene, is also key․

Mutations, changes in the DNA sequence, are a significant source of genetic variation․ These can be point mutations (substitutions, insertions, deletions) or chromosomal mutations․ The impact of mutations – beneficial, harmful, or neutral – will be explored․

Furthermore, the topic covers Chargaff’s data relating to base pairing in DNA, and how variations in base composition can occur in different organisms, like Mycobacterium․ Understanding these concepts provides a foundation for inheritance patterns and evolution․

3․2 Meiosis

Meiosis is a specialized type of cell division crucial for sexual reproduction, reducing the chromosome number by half to produce gametes (sperm and egg cells)․ This process ensures genetic diversity in offspring․

The stages of meiosis – Prophase I, Metaphase I, Anaphase I, Telophase I, and then Prophase II, Metaphase II, Anaphase II, and Telophase II – will be detailed, emphasizing the key events in each phase․ Crossing over during Prophase I, a vital source of genetic recombination, will be thoroughly examined․

Students will learn to compare and contrast meiosis with mitosis, highlighting the differences in chromosome behavior and the resulting daughter cells․ Understanding independent assortment and its contribution to genetic variation is also essential․

The link between meiosis and the concepts of genes, chromosomes, and mutations, previously studied, will be reinforced․ Errors in meiosis can lead to aneuploidy, impacting offspring viability, and this will be discussed․

3․3 Inheritance Patterns

Inheritance patterns explore how traits are passed from parents to offspring․ This section delves into Mendelian genetics, including monohybrid and dihybrid crosses, utilizing Punnett squares to predict genotypic and phenotypic ratios․

Beyond simple dominance, students will investigate incomplete dominance, codominance, and multiple alleles, understanding how these alter expected ratios․ Sex-linked inheritance, focusing on X-linked traits, will be examined, explaining differing inheritance patterns in males and females․

The concept of polygenic inheritance, where multiple genes contribute to a single trait, will be introduced, explaining continuous variation․ Epistasis, where one gene masks the expression of another, will also be covered․

Understanding Chargaff’s data relating to DNA base composition will provide context for genetic variation․ Pedigree analysis, used to trace traits through generations, will be a key skill developed, allowing prediction of inheritance risks․

Ecology

Ecology, the study of interactions between organisms and their environment, forms a crucial component of IB Biology HL․ This section begins with species and populations, examining population growth curves, carrying capacity, and factors influencing population size – birth rates, death rates, immigration, and emigration․

Moving to communities and ecosystems, students will analyze trophic levels, food webs, energy flow, and nutrient cycles․ Primary and secondary succession, alongside the roles of keystone species, will be explored․ Understanding gross and net primary productivity is essential․

The final area focuses on biomes and conservation․ Different terrestrial and aquatic biomes will be studied, considering their climate, characteristic organisms, and adaptations․ Conservation biology, including threats to biodiversity, and strategies for conservation, will be emphasized․

This includes understanding human impacts on ecosystems and the importance of sustainable practices․ Ecological data analysis and interpretation are vital skills developed throughout this topic․

4․1 Species and Populations

Species and Populations, the foundational element of ecological study, requires understanding how and why populations fluctuate․ Key concepts include defining a species – utilizing the biological species concept – and exploring factors impacting population growth․ This involves analyzing birth rates, death rates, immigration, and emigration․

Students will learn to interpret population growth curves, differentiating between exponential and logistic growth models․ The concept of carrying capacity – the maximum population size an environment can sustain – is central․ Limiting factors, both density-dependent and density-independent, will be examined․

Furthermore, understanding population distribution patterns – clumped, uniform, and random – is crucial․ Age structure diagrams provide insights into a population’s potential for future growth․ Investigating these dynamics provides a basis for understanding broader ecological interactions․

4․2 Communities and Ecosystems

Communities and Ecosystems build upon population studies, focusing on interactions between species and their non-living environment․ Key concepts include understanding community structure – species richness, evenness, and dominance – and the roles organisms play within a community, such as producers, consumers, and decomposers․

Students will explore various interspecific interactions: competition, predation, mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism, analyzing their impact on population dynamics․ Trophic levels and food webs illustrate energy flow through ecosystems, with emphasis on the 10% rule and ecological pyramids․

Understanding nutrient cycles – carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus – is vital, as is examining the role of ecosystems in providing essential services․ Ecosystem resilience and succession, the process of change over time, are also core components․ Analyzing these interactions reveals the interconnectedness of life․

4․3 Biomes and Conservation

Biomes represent large-scale ecosystems characterized by specific climate conditions and dominant vegetation․ Studying biomes – such as tropical rainforests, deserts, grasslands, and tundra – involves analyzing adaptations of organisms to their unique environments and understanding global distribution patterns․

Conservation biology addresses the preservation of biodiversity, facing threats like habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, and climate change․ Students will investigate the impact of human activities on ecosystems and explore conservation strategies, including protected areas, restoration ecology, and sustainable resource management․

The concept of ecological footprint highlights human demand on Earth’s resources․ Examining case studies of endangered species and conservation efforts demonstrates the complexities of balancing human needs with environmental protection․ Understanding the interconnectedness of biomes and the importance of biodiversity is crucial for effective conservation․

Internal Assessment (IA) Guidance

The IA demands a scientifically sound investigation․ It’s structured around design, data collection/processing, and a robust conclusion with thorough evaluation of methods and results․

IA Design Principles

A strong IA begins with a well-defined research question, focused and investigable through experimentation․ This question should clearly articulate the relationship between variables – independent, dependent, and controlled․ Thorough background research is crucial, demonstrating understanding of relevant biological concepts and existing literature․

The experimental design must be appropriate to address the research question, considering controls to minimize bias and ensure validity․ Precise methodology, including detailed procedures and materials lists, is essential for reproducibility․ Risk assessment and ethical considerations are paramount, ensuring safety and responsible scientific practice․

Data collection methods should be justified and appropriate for the variables being measured․ Sample size needs careful consideration to ensure statistical power․ A clear plan for data processing and analysis, including appropriate statistical tests, is vital before commencing the experiment․ The checklist emphasizes essential questions to guide this design phase, ensuring a robust and scientifically sound investigation․

Data Collection and Processing

Meticulous data collection is fundamental to a successful IA․ Records must be comprehensive, including all raw data, observations, and any unexpected occurrences during the experiment․ Data should be organized systematically, often using tables and clearly labeled columns and units․ Accuracy and precision are paramount; repeat measurements and appropriate calibration of instruments are vital․

Data processing involves transforming raw data into a usable format for analysis․ This may include calculating averages, percentages, or rates․ Appropriate graphing techniques – line graphs, bar charts, scatter plots – should be selected to visually represent the data and highlight trends․ Error analysis, including identifying potential sources of error and their impact on results, is crucial․

Statistical analysis is often necessary to determine the significance of findings․ Selecting and applying appropriate statistical tests, justified by the nature of the data, demonstrates a strong understanding of scientific methodology․ The checklist guides students through essential questions regarding data handling and analysis, ensuring rigor and validity․

The conclusion should directly address the research question, summarizing the key findings and stating whether the hypothesis was supported or refuted․ It must be based solely on the processed data, avoiding extraneous information or speculation․ A clear and concise restatement of the main results is essential, linking them back to established biological knowledge․

Evaluation is a critical component, demanding a thorough assessment of the investigation’s strengths and weaknesses․ Identify limitations in the methodology, potential sources of error, and their impact on the reliability of the results․ Suggest specific improvements to the experimental design for future investigations․

Consider the validity of the conclusion in light of the evaluation․ Discuss whether the findings are generalizable or limited to the specific conditions of the experiment․ The IA checklist emphasizes evaluating the quality of data, the appropriateness of the methods, and the overall scientific rigor of the investigation, ensuring a comprehensive self-assessment․